NIGHT ON EARTH

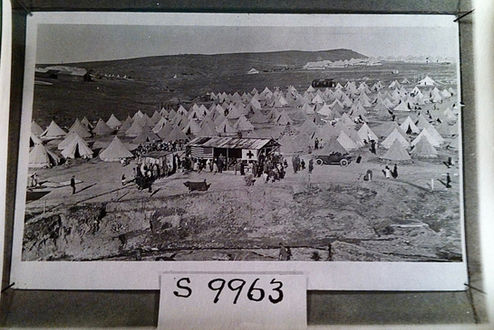

Night on Earth. A History of International Humanitarianism in the Near East, 1918-1930 examines cases when, in the aftermath of the First World War, short-term relief programs aimed at providing food, shelter, clothing and basic medical aid – a bed for the night, to use David Rieff’s phrase – to distressed civilian populations turned into ante-litteram development projects or state-building attempts. My argument is that in the 1920s and 1930s, European and American humanitarian associations undertook programmes that went beyond relief. The tentative title of the book is a clin d’oeil to Jim Jarmush’s 1991 eponymous movie since the events I write about took place at the same time in different geographical areas.

The institutions I study defined their humanitarianism as encompassing a continuum between relief and rehabilitation and, sometimes, they set up agricultural, educational, public health programmes. Breaking conventional historiographical caesuras, I argue that ‘development’ programmes undertaken by international agencies existed well before 1945 and the birth of the United Nations. Development revolved around the principle of ‘self-help’, which contested older ideas of charity. Contrary to the idea of self-empowerment, seen today as the opposite of social engineering, early-twentieth century humanitarian actors saw self-help as an essential ingredient of their social engineering ambitions and as a way to ensure peace and prosperity in the areas in which they operated.

‘Progressive’ inter-war international humanitarians ‘administered relief’ in ‘modern’ ways and used discourses similar to post-1945 relief and development agencies. Their programmes were undertaken in areas the protagonists of my story viewed as ‘under-developed’, ‘semi-civilised’ or ‘barbarous’. In areas where state sovereignty was conspicuously deficient, these institutions were tempted to ‘play God’ – literally to decide over life and death of civilian populations. The protagonists of my book imagined the thick line that went from the Baltic Sea and Poland to the Balkans (beyond which Bolshevik territory began) and continued farther east in Turkey, Syria and Palestine as the ‘faultlines of Western civilisation’.

The idea that humanitarian actions performed abroad have domestic or colonial roots is certainly not new. However, the account of how ideas that germinated in Western Europe or the United States were adapted in Eastern Europe, in South-East Europe and the Near/Middle East has not yet been explored. The protagonists of my book are a group of secular and religious international associations (the predecessors of today’s NGOs) based in Europe and the U.S.: inter-governmental organisations and philanthropic foundations such as the American Relief Administration, the American Red Cross, the Near East Relief, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the American Women’s Hospitals, the Rockefeller Foundation, the League of Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Quakers, Save the Children, the Union Internationale de Secours aux Enfants, YMCA/YWCA and the women and men that worked (as volunteers or in a professional capacity) for all these institutions in various regions of Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe and in the Near and Middle East, with an emphasis on Greece, Turkey, the Caucasus, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. They certainly are a heterogeneous group of institutions that nevertheless shared ideas on internationalism (peace and prosperity), nationalism (nation- and state-building), and international law. For this reason I work on them as configurations of actors.

Focusing on their ‘humanitarian’ programmes I compare actors who did not define themselves as being primarily humanitarian; I engage with different conceptualisations of humanitarianism (and ‘humanitarian missions’); and I consider the emerging self-understanding of nascent humanitarian organisations. I use a transnational history approach based on a multi-archival research from European or American organisations or Western state archives. The book takes the perspective of the supply-side of humanitarian actions; it is not a history from the margins or a bottom up history. Still, it critically addresses the many silences of humanitarian organisations’ archives and the defective visions they produce by telling stories of ‘saved’ individuals, ignoring those of the masses of ‘drowned’ civilians.

The work explores the meanings of international humanitarianism – which often blended secular and religious dimensions, imperialist impulses, and eugenic, racist or civilisational assumptions. Rather than merely condemning paternalism and colonial postures of the institutions under scrutiny, the book examines the interweaving of these dimensions with humanitarians’ ‘good intentions’ in given geographical areas from the late 1910s to the 1930s. I endeavour to find a historical explanation of how self-proclaimed responsibilities, individual or institutional motivations, manifested themselves in a variety of relief and re-constructive actions encompassing social engineering, often delusional, dimensions.

My research has a broader purpose: I wish to avoid the history and politics of humanitarianism to turn into a parochial and self-referential field of study. I wish to connect it with contiguous historiographies and histories: political and diplomatic, social and culture, gender, colonial and imperial. My research is informed by other disciplines such as international law, political science and anthropology. I wish to know more about the 21 grams, i.e., the specific weight of this ever-controversial –ism. I am persuaded that humanitarian-centric accounts are incorrect and fail to adequately contextualise humanitarian actions. The significance of the project lies in its contribution to our understanding of the history and politics of Western humanitarianism, humanitarian and/cum development aid. I hope my research will be relevant for scholars interested in the history of the twentieth century, of non-state actors and of international organisations, of Western humanitarianism and of human rights.